By Sara Hesselsweet | January 2020

Because our family skis with touring equipment, we have the ability to free-heel. For many folks, the objective of alpine touring involves climbing up slopes that aren’t accessible by lifts so you can then ski lines inaccessible to resort skiers, often in remote locations and/or untracked powder.

But backcountry skiing isn’t solely about extreme terrain or steeps – there is so much land out west to explore in all seasons, including such a wide variety of terrain and ski objectives. We would love to one day ski Craters of the Moon National Monument and Yellowstone NP (these and other public lands will close roads in the winter, making them ideal places to explore by snowshoe or ski). So we’re gaining experience with free-heel traverses, working on making our strides and posture more efficient and our increasing comfort on undulating and variable terrain – it’s not easy to navigate a downhill portion of a trail with your heel free unless you are well-practiced! Touring skis = winter freedom.

Officially, alpine touring skis are a subtype of Nordic ski – Nordic skiing refers generally to free-heeling. Other styles of Nordic skiing are telemark and cross-country – these have different boots, bindings, and techniques. What all these skis have in common is that they allow you to traverse distances on snow independently of resort-operated lifts.

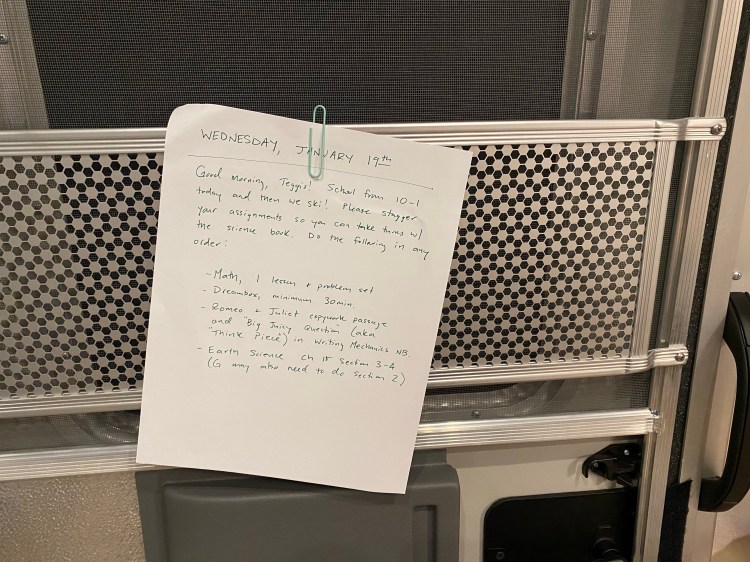

One day in Breck I decided to ascertain how feasible it would be to use our touring ski setups on actual cross-country ski trails – and what techniques would work best. I have cross-country skied once before with my aunt and uncle who live in Estes Park and recall it being extraordinarily fun but also very challenging, and I wanted to brush up on my technique and learn a little more. So I left the kids with some assignments to work on back at the Airstream (the homeschool equivalent of a sub plan) and made myself an appointment for a cross-country skiing lesson at the Breckenridge Nordic Center.

Because an alpine touring ski setup is a little different from cross-country skis, it would take some inventiveness to make this work. I try not to be a purist about gear or techniques – skiing has evolved over millennia from its origins as an early mode of human transportation and as such, I think it should be embraced in more practical and accessible ways. The modern conception of skiing as a luxury sport relegated to resort areas with expensive high-tech gear is incomplete. When we visit museums (like the Breckenridge Visitor Center or the Treads of Pioneers museum in Steamboat Springs) and look at skis from a century ago, we marvel at how sturdy humans figured out how to navigate snow-covered terrain on what were essentially planks of wood they strapped to their shoes – opening up a whole new world of winter possibilities. Fortunately, I had a terrific instructor at the Breckenridge Nordic Center who shared my scrappy attitude and was happy to help with my unorthodox experiment.

Here’s what I learned from my instructor, who cross-country skied in college in Wisconsin and now lives in Denver, commuting to Breck one day a week to teach at the Nordic Center. Traditionally, there are two styles of cross-country skiing. Skate-skiing is a more intense and full-body movement not unlike how downhill skiers sometimes navigate flats around base areas, with really aggressive poling and a wider stance. Skis for this style of skiing have no grip on the bottom, so to climb hills, skate-skiers have to aggressively push off each ski, keeping it at an angle to avoid slipping back downhill. Momentum helps too, so you are thinking about using terrain to optimize speed. Trails groomed for Nordic skiing have a wider area of flat corduroy for skate skiers, and to one or both sides will be deep grooves for classic cross-country skiers, who keep their skis in the tracks and use only a parallel/forward gliding motion. Classic cross country skis have some grip underfoot to allow them to climb hills – but the rest of the ski is smooth to allow glide.

By contrast, touring ski setups have adjustable bindings (with uphill/free-heel or downhill/locked modes) and removable full-coverage skins, allowing you to climb steeper slopes with your skins on and heel free and then “transition” at the top of the slope, removing the skin and locking in your heel for the descent. Cross-country skis have no such transition; they’re optimized for trails with a smaller range of slope angles (less steep, in other words a less extreme ascending/descending differential). Emma’s Baldy Ridge post offers her take on the uphill/downhill transition process that is unique to alpine touring equipment!

My instructor gamely offered suggestions for navigating trails using different techniques and gear settings and we experimented to determine what worked best. Of all the variations, I found that keeping the skins on and staying in the parallel tracks allowed for easy climbing/walking but slower progress in terms of covering distance (much less glide since my skins cover my entire ski) and that skate-skiing (no skins, heel free) was the hardest technique to master especially on inclines/declines and the most intense in terms of cardiovascular output but offered the best potential for covering flatter terrain quickly.

I loved how cross-country skiing juxtaposes a tranquil atmosphere with high-intensity exercise… Ideal for cultivating both winter mental health and VO2 max! In fact the skate-skiing caused my Garmin to recommend that I spend the next two days recovering. I may one day have to add proper cross-country skis to the quiver.

Later in the afternoon, I scooped up Tim and the kids and we headed into Breck for some regular old freezing-cold resort laps on Peak 6 and Peak 7. To stay warm on the lifts, we discussed the day’s lessons… Where in the story of Romeo and Juliet things all went wrong – which if any character bore the ultimate responsibility? Of course we all had different opinions on this! Finished the day with our best effort at covid-friendly apres-ski – hot soup and pie from Whole Foods and some local IPAs for the parents.