By Graham Hesselsweet | January 2022

For years, I had gazed into mountain faces, searching out ski lines and wondering what adventure there was to be had when you dared to exit the boundaries of ski resorts, increase slope angles, and seek out powder stashes.

But before it’s safe to venture into the backcountry in the winter, it’s necessary to have the proper knowledge and equipment to be responsible for your own safety. That’s why my mom and I planned to take the AIARE level 1 course while we were in Summit County, Colorado. We signed up for a weekend with Apex Mountain School, who we’d also used for a backcountry tour at Fremont Pass the weekend before.

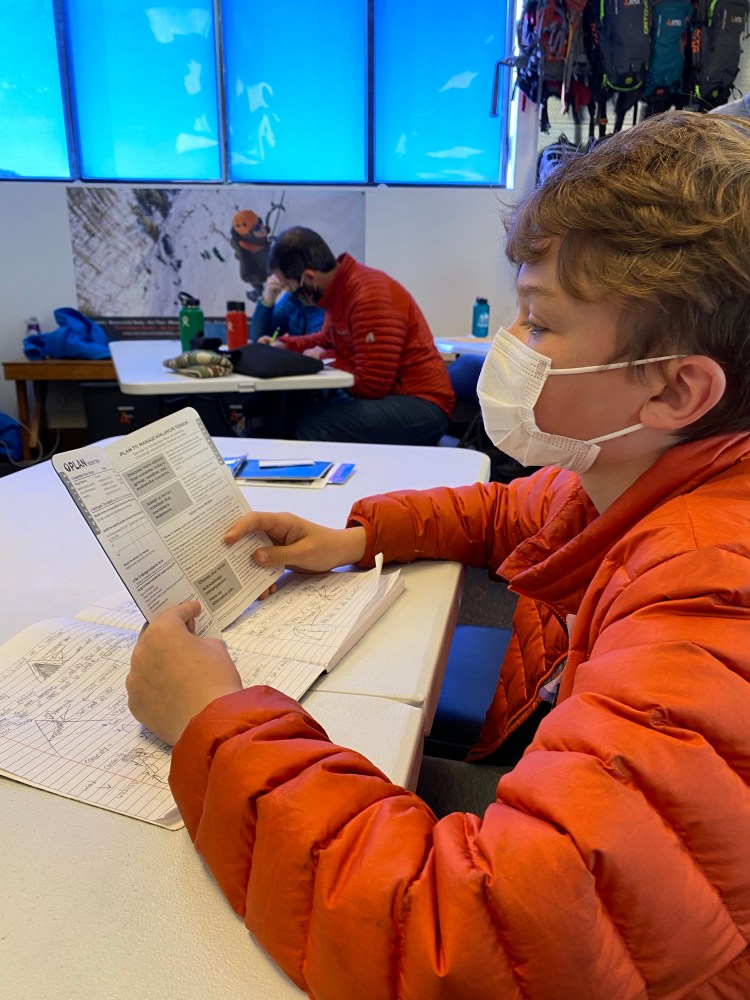

AIARE is the American Institute for Avalanche Research and Education. Their stated purpose is to “create a researched-based avalanche education model for back-country users with the belief that avalanche education, research, and training can prevent injuries and fatalities due to avalanches. Now, I was 12, the minimum age to participate in the AIARE course, which would allow me to join the ranks of backcountry adventurers. My mom and I had been looking forward to this immersive and intensive weekend since we signed up half a year prior. We would spend Friday in the classroom and both weekend days in the field with our instructor and a small group of fellow backcountry enthusiasts. We prepared for our three-day class with a week of online learning modules.

AIARE is at its core a framework for making evidence-based decisions and risk-taking in the backcountry. The AIARE level 1 course introduces participants to snow science, weather, types of avalanche problems, and terrain information, but the most important element is arguably human decision-making factors that influence safety in the backcountry. Other than terrain, human heuristics are a major source of control and influence in determining your safety in the backcountry. The psychology of how people behave socially, trying to make decisions in a group of peers, is very interesting. Even knowledgeable skiers have made fatal mistakes because they for some reason didn’t speak up when they felt uncomfortable. One of our big takeaways was the importance of creating a culture where people are willing to speak up and a “culture of listening”. Our guide Mike says “Culture eats planning for breakfast.”

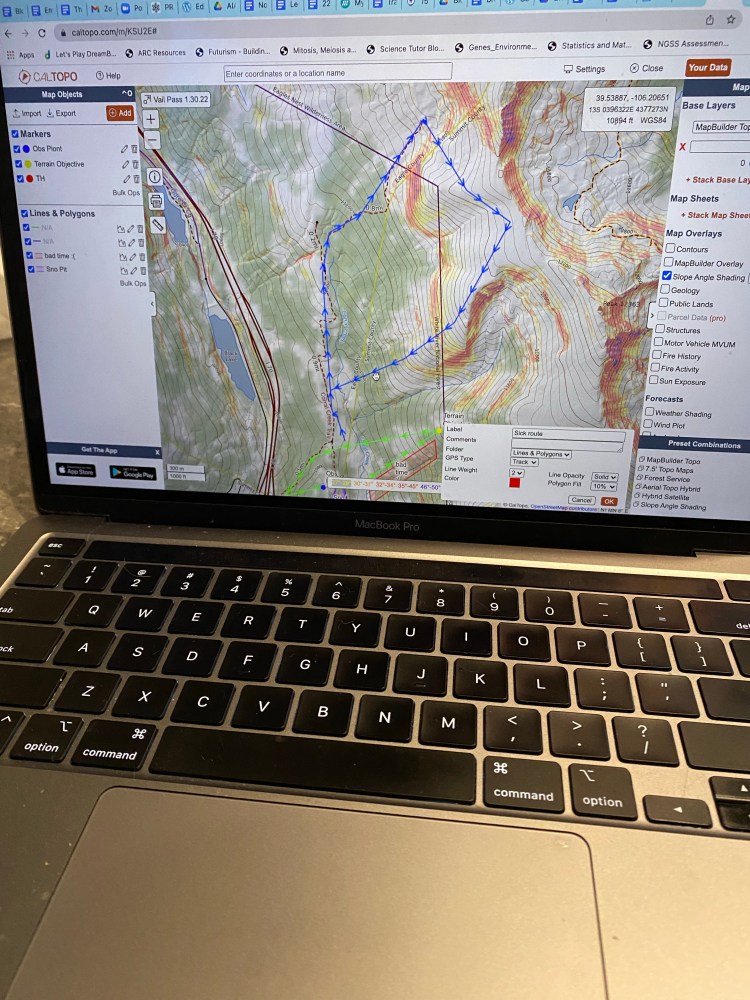

Planning is important too. We also learned that embarking on a trip into the backcountry is foolish without a plan recorded in your AIARE field notebook and agreed upon by each member of the group and supported by well-practiced navigation and route-finding skills. Under the knowledgeable supervision of our instructors, we learned how to plan routes using topographical maps in CalTopo and maintain our maps in Avenza, which allows GPS navigation without a wireless signal. We learned to read the subtleties of contour lines that would indicate terrain traps, cliffs or areas that could be avalanche-prone. Avalanches tend to occur on slopes between 30 and 45 degrees, and we use both inclinometers and topographical map data to identify safe slope angles. And the fun part — we learned to identify safely skiable ridgelines and use satellite images to find nicely spaced glades to plan our ski descents.

Should you ever find yourself in dangerous territory, your best-laid plans having gone awry, you should know that escaping an avalanche can be difficult but is possible. I’ll offer an insider tip: If the snow below you starts to slide, ski away fast to the side. A technique called “slough management” is even a strategy for skiing steep slopes, if your risk tolerance is high. Slough management is creating tiny avalanches, and zigzagging while avoiding the avalanches as they cruise past you. Always yell “avalanche!” to alert others in your party. Keep eyes on anyone down the slope so if you see them get buried you can be quick to the scene. And of course, carry a beacon, probe, and shovel at all times. You never know when you will be called upon to rescue a fellow backcountry adventurer.